Quantifying Islamic Law in the Modern State

Horizon Marie Skłodowska-Curie Action, Project Number 101106259

Ari Schriber

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Dataset at a Glance

- Key Findings

- Understanding Islamic Law as Tradition

- The Supreme Council of Shari’a Appeals (SCSA, 1921-1957)

- Text Mining Methodology

- Results and Analysis

- Other Select Terminology

- Acknowledgements

- Appendix: Complete List of Sources Identified in 777 SCSA Cases, 1921-1957

Introduction

Islamic law endures as a critical component of legal systems in the Middle East and North Africa. The specific role of Islamic law in state courts remains intensely contested by scholars, policy makers, and activists alike. The project “Quantifying Islamic Law in the Modern State” embraces these debates to interrogate the role of Islamic textual tradition in courts. The rules of Islamic law are outwardly based on a centuries-old tradition of legal texts, yet since the late-nineteenth century, Muslim-majority polities worldwide have legislated codes to standardize its rules. The state-imposed codification of Islamic law has gained immense attention from scholars who question whether a religious tradition can truly exist as state legislation. However, such lines of inquiry predominantly account for Islamic law by highlighting discrepancies between classical Islamic legal texts and state codes. Stakeholders of Islamic law have little indication of how judges themselves determined Islamic law-based rulings in the courtroom in modern states. This issue raises a deeper question with critical implications for the future of religious law: to what extent does Islamic law transform if state legislators—and not religious scholars—dictate its functioning?

This project contends that understanding the impact of modern state institutions requires understanding Islamic law in the era prior to them. “Quantifying Islamic Law” uses statistical text analysis to reconstruct Islamic legal tradition in court practice prior to state codification of shari’a. It does so in the context of Morocco, a nation with a rich Islamic legal tradition and a contemporary government that claims to uphold it through codified family law. Using a corpus of 777 judgements issued by the Supreme Council of Shariʿa Appeals from 1921-1957, “Quantifying Islamic Law” tracks references to core sources of Islamic legal tradition: jurists and their texts. The cumulative data from this corpus of judgements provides a new quantitative basis for understanding the most important sources of Islamic law as invoked by judges in twentieth-century Morocco.

*Note: The results presented below should not be understood as a comprehensive statement about “what is” Islamic law, as privileging text over practice, or as applicable beyond the dataset’s regional, geographic, and institutional context. The text analysis provides a quantitative basis to affirm or modify qualitative characteristics of Islamic legal tradition as construed in this context. Future updates will expand the data set and its analysis.

Dataset at a Glance

- Total cases in the dataset: 777 (issued from 1921 to 1957)

- Total jurists mentioned: 212 (plus the Qur’an and Hadith = 214 sources)

- Total cases mentioning at least one legal source: 659 (84.8%)

- Average number of indiviudal sources mentioned per case: 4.72

- *Geographic origin of cases:

*Map includes 690 cases due to case records where the origin is not identified or ongoing research is needed (e.g., to identify tribal geography).

- List of Top Ten Jurists Mentioned (by total cases mentioning them at least once)*

| Name (common name bold) | Death Date (Islamic) | Death Date (Gregorian) | Origin | Textual Genre (Primary*) | Cases Mentioning | Percentage of Cases Mentioning (of 777 total cases) |

| Khalīl b. Isḥāq al-Jundī | 767 | 1365 | Egypt (Cairo) | “Abdrigement” of Mālikī legal rules | 363 | 46.72 |

| Ibn ʿĀṣim, Abū Bakr Muḥammad b. Muḥammad | 829 | 1365 | Andalus (Granada) | Versified manual of judgeship | 321 | 41.31 |

| al-Tasūlī, Abū al-Ḥassan ʿAlī b. ʿAbd al-Salām | 1258 | 1842 | Morocco (Fez) | Commentary on Ibn ʿĀṣim’s manual | 227 | 29.21 |

| al-Zaqqāq, Abū al-Ḥassan ʿAlī b. al-Qāsim al-Tujaybī | 912 | 1507 | Morocco (Fez) | Versified collection of judicial practice (‘amal) of Fez | 180 | 23.17 |

| al-Zurqānī, ʿAbd al-Bāqī b. Yūsuf | 1099 | 1688 | Egypt (Cairo) | Commentary on Khalīl’s abridgement | 139 | 17.89 |

| al-Wansharīsī, Abū al-ʿAbbās Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā | 914 | 1508 | Morocco (Fez) | Precedent legal opinions (nawāzil) | 124 | 15.96 |

| al-Rahūnī, Muḥammad b. Aḥmad | 1230 | 1815 | Morocco (Fez) | Super-commentary on al-Zurqānī’s commentary on Khalīl’s Abridgement | 106 | 13.64 |

| Ibn Rushd (al-Jadd), Muḥammad b. Aḥmad | 595 | 1198 | Andalus (Cordoba) | Legal opinions (fatwās) | 105 | 13.51 |

| Saḥnūn, Ibn Ḥabīb al-Tanūkhī | 240 | 854-5 | Tunisia (Qayrawan) | Collection of legal norms attributed to Mālik b. Anas. | 90 | 11.58 |

| al-Tāwūdī b. Sūda al-Mārī, Muḥammad b. Muḥammad | 1209 | 1794-5 | Morocco (Fez) | Commentary on al-Zaqqāq’s manual Commentary on Ibn ʿĀṣim’s manual Super-commentary on al-Zurqānī’s commentary on Khalīl’s abridgement | 86 | 11.07 |

*For authors with multiple texts, the text(s) listed constitute the majority of citations.

Key Findings

Dominance of Khalīl’s Mukhtaṣar and Ibn ʿĀṣim’s Tuḥfa: By far, the two most frequently cited texts are the Mukhtaṣar of Khalīl b. Isḥāq al-Jundī (d. 767/1365, Egypt) and Ibn ʿĀṣim’s (d. 829/1426, Granada) Tuḥfat al-ḥukkām fī nukat al-ʿuqūd w’al-aḥkām. The Mukhtaṣar is a concise “abridgement” or “restatement” of Mālikī legal rules that has predominated Islamic legal practice in the Maghrib for the past five centuries. The Tuḥfa is a versified manual of judicial practice serving as a guide for adjudicating various elements of court cases. Each text received numerous commentaries and super-commentaries that judges often cited in their cases.

Diversity of authorship and genre: The 200+ cumulative jurists (and their texts) identified in the dataset range significantly by time period, geographic origin, and author function (e.g., commentator, compiler, or giver of opinions). Judges did not focus only on the most famous classical manuals of Islamic law or the Mukhtaṣar and Tuḥfa. Rather, they also frequently mentioned jurists who compiled precedent legal opinions (nawāzil), judicial practice of Fez (ʿamal Fās), and documentation manuals (wathāʾiq).

Robust “Early-Modern” Moroccan Scholarship: judges relied on a prolific scholarly output of Moroccan jurists from approximately the 16th-19th centuries. Historiography of Islamic law long presumed this period as merely derivative or marginal to the more famous classical texts. This project’s data shows that the 20th century judges frequently mentioned Moroccan jurists of from this period, led by al-Tāwūdi, al-Rahūnī, and al-Sijilmāsī. These authors not only explained earlier texts like the Tuḥfa or Khalīl’s Mukhtaṣar but rearticulated them for their contemporary and local context.

Discernable changes, 1921-1957: The quantitative results reveal few changes with respect to jurist mentions across the three-plus decades of the SCSA’s existence. In most cases, those who were most popular in the 1920s remained so in the 1940s and 50s. Several changes do occur in the substance of cases, including the gradual decline of Jewish litigants, disappearance of issues involving slavery, and the increased citation of Protectorate-era legislation.

Understanding Islamic Law as Tradition

“Quantifying Islamic Law” benefits from decades of historiographical correctives in the study of Islamic legal history. Fortunately, historians of Islamic law have transcended old clichés about Islamic law’s immutability, doctrinaire archaism, and/or whimsical application. These scholarly interventions have led to several conceptual advances that directly inform this project:

Islamic law as discursive tradition: the anthropologist Talal Asad famously characterized Islam writ large as a “discursive tradition” based on how Muslims themselves understand Islam: as constructed through a historical discourse. Asad’s conceptualization transcends scholarship that portrays Islam as either bound to classical doctrine or simply whatever Muslims say it is. Notwithstanding the qualifications to Asad’s concept, SCSA cases show that judges very much understood Islamic law as a discursive tradition in Asad’s sense. For this reason, this project analyses Islamic law as a historically constructed tradition as judges themselves constructed it.

Beyond classical sources: historians also have thoroughly debunked notions that Islamic law had not substantively changed for centuries and remained derivative of “classical” sources. Scholars thereafter established that textual traditions are particular to place and space, with new texts building on, perpetuating, and/or altering traditions. The results of “Quantifying Islamic Law” speak to the importance of texts beyond the Islamic legal school’s most famous classical manuals of substantive law (furūʿal-fiqh) or legal methodogies (uṣūl al-fiqh). Compilations of precedent fatwās (nawāzil), collections of local judicial practice (ʿamal), and manuals of documentation (wathāʾiq) all figure as integral normative components of Islamic legal tradition applied by twentieth-century Moroccan judges.

Textual tradition and court practice: historians and anthropologists have struggled to characterize Islamic law in court practice. No serious scholar accepts Max Weber’s notion of kadijustiz outright, which portrays the Islamic judge as producing arbitrary decisions motivated by expediency. At the same time, historians and anthropologists have noted that courts do not simply mirror prescriptions of “prestige” Islamic legal texts. Scholars who have examined Islamic court practice on its own terms, whether by archive or ethnography, therefore have sought to understand the relationship of judicial discretion to Islamic textual tradition. “Quantifying Islamic Law” understands this relationship as contingent on the judicial body and/or judge in question. SCSA case records demonstrate the variable relationship of text and social discretion as judges produce rulings.

State Codification of Shari’a: the issue of state codifications of Islamic law has garnered enormous scholarly attention in recent decades. If modern state authorities supplanted Islamic juristic practice, how—if at all—Islamic law could exist in state-legislated form? No state-legislated code existed in Islamic legal contexts until the late-nineteenth-century promulgation of Ottoman legal codes, including the 1876 Mecelle code of civil law and the 1917 Family Code. In British colonial contexts, British judges applied a hybrid “Anglo-Mohammadan Law” that included substantive Islamic legal concepts adjudicated by English judges. In Morocco, colonial-era legislation like the 1913 Code of Contracts and Obligations included some transactional concepts based on Islamic law. It was only in 1957—one year after independence—that Moroccan legislators enacted a code explicitly based on Islamic law. This legislation, the Code of Personal Status (later the “Code of Family Law”), comprised matters of marriage, divorce, paternity, inheritance, and tutorship. “Quantifying Islamic Law” therefore situates the SCSA archive as a critical view into Islamic legal tradition in courts on the eve of state codification.

The Supreme Council of Shari’a Appeals (SCSA, 1921-1957)

The dataset that this project uses comes from records of the Supreme Council of Shariʿa Appeals (1912-1957). In order to better understand the corpus of cases included in this study, it is necessary to understand the Council’s history, function, and use as a dataset.

History: The 1912 Treaty of Fez formalized the French Protectorate of Morocco on the premise that France would reform Moroccan institutions in formal cooperation with the sultan. Legislation thereafter came via the traditional royal decree (ẓahīr sharīf) co-signed by both the sultan and the French Resident General. The first resident general Hubert Lyautey propounded a policy of “indirect rule” by formally preserving pre-existing institutions, especially those relating to Islam and the sultan. However, formally preserving shari’a courts did not exempt them from substantial reforms.

In the first years of the Protectorate, large swaths of legislation by royal decree rearticulated jurisdiction by ethnic, religious, and national identity, promulgated new codes for commerce and land tenure, and stipulated new judicial procedures under the pretext of administrative improvement. Protectorate-era shari’a courts remained competent for personal status issues—e.g., marriage, divorce, paternity, and inheritance—for Moroccan Muslims, as well as issues of real property outside of the Protectorate’s new regime of land registration. Shariʿa courts were also subject to a new appellate body of last resort: the Supreme Council of Scholars (SCS, Majlis al-ʿulamāʾal-aʿlā). Established in 1913, the SCS was comprised of three Islamic legal scholars under the singular control of minister of justice and renowned jurist, Abū Shuʿayb al-Dukkālī. In the following years, Protectorate officials became increasingly uncomfortable with al-Dukkālī’s nearly unchecked judicial and ministerial power.

The Royal Decree (ẓahīr sharīf) of February 7, 1921 replaced the Supreme Council of Scholars with the newly constituted Supreme Council of Shariʿa Appeals. The Council originally consisted of two chambers (later four) with three judges each, all of whom fell under the leadership of the chief judge. The case records of the SCSA and contemporaneous observations indicate that the chief judge played a decisive role in the Council’s rulings. Across its 36-year history, some of Morocco’s most renowned jurists held the position of chief judge, including Muḥammad al-ʿArabī al-ʿAlawī, Aḥmad ʿAwād, and Muḥammad al-Ḥajwī. French archival sources note that appeals submitted to the SCSA increased significantly across the 1920s, indicating its rapid entrenchment in the Moroccan legal field. The SCSA persisted until 1957, when it was replaced by the newly independent nation’s Supreme Court.

Functioning: the SCSA received appeals from the losing party of a dispute before a local shari’a court. Litigants from smaller shari’a courts also could appeal first to a regional urban judge of first appeal until 1939, when all shari’a court appeals came directly to the SCSA. Protectorate functionaries ensured that appeals dossiers were complete, including copies of the original judge’s ruling and associated legal documents (e.g., contracts and testimonies) before delivering the dossier to the Council. It is nonetheless difficult to ascertain the precise inner workings of the Council between their reception of the dossier and the final ruling. In some instances, the Council addressed the original judge to undertake missing procedures (e.g., oaths or testimony validation) before issuing its ruling, missives that are preserved in the case rulings.

The SCSA could uphold, annul, and/or remand the case to the original judge for further procedures before the final ruling. The judgements often recount individual parts of the original ruling to pronounce the Council’s ruling on each respective part. When upholding a given ruling, the records most often use the terms ṣaḥīḥ (valid), ṣawāb (correct), or fī maḥallihi (“in its [correct] place”). Conversely, it reversed rulings interchangeably using terms bāṭil (null and void), naqḍ (annulled), or fī ghayr maḥallihi (“out of place”). The Council often remanded cases to the original judge for further information or ordering them to undertake missing procedures before issuing its final ruling.

SCSA Judgements as Dataset:

The content of the records, while varying in length, are a comprehensive summary of the proceedings from beginning to end, including:

- The original claim: the plaintiff’s petition (maqāl) to the local shari’a court and request for justice, including specific places, names, and dates.

- Pleadings: the defendant’s response (jawāb) to the claim; litigant presentation of proofs (ḥujjaj), including relevant testimonies and/or contract documents; litigant presentation of juristic opinions (fatāwā) supporting their claim; the right of response to opposing proof (iʿdhār); the assignment of any oaths (aymān).

- Judge’s ruling: a final pronouncement on the original claim, with varying degrees of explanation. To the extent that judges mention the Islamic legal sources analyzed below, it occurs in this portion.

- First appeals ruling: prior to 1939, litigants could appeal shari’a court rulings to shari’a courts of urban centers before appealing to the SCSA. After 1939, Protectorate legislation stipulated that all shari’a court appeals directly to the SCSA.

- Appeal to SCSA: summary of original proceedings; any necessary further actions before the original judge (e.g., missing information or procedures); pronouncement on the original ruling with varying degrees of explanation, including citation to relevant Islamic legal texts. Since over 80% of the case records mention at least one jurist, these explanations provide excellent insight into the judicial conception of Islamic legal tradition.

It is hoped that more cases can be added to the dataset in the future along with the cases from the earlier Supreme Ulama Council (1913-1921).

Text Mining Methodology

The cases comprising this study were made available by the contemporary Moroccan Court of Cassation and the Moroccan Ministry of Justice. Since 1999, the Ministry’s publishing house has printed ten individual volumes of SCSA rulings (Volumes I, II, II Books 3-4, IV, VI, VII, VIII, IX, and X), each corresponding to an original handwritten ruling book (kunnāsh). The individual books are categorized by topic, though the rulings are rarely reducible to a single substantive issue. In addition to 722 printed rulings, this project accessed original handwritten rulings, 55 of which were transcribed for the dataset, giving a total of 777 rulings in this project’s dataset. Each notebook is comprised of individual case records denoted by an SCSA case number and original dispute number. Qualitative examination of the original SCSA rulings in the Supreme Court library confirms the accuracy of the printed versions while also confirming that there are unprinted rulings in the original notebooks.

“Quantifying Islamic Law” uses statistical text analysis in order to extract data from a text corpus of 777 SCSA records. Most relevantly, this data includes the frequency with which judges mentioned sources—i.e., jurists and/or their texts—in their rulings. The primary metric that the project adopts for tracking these sources is total cases mentioning a jurist (or their texts) at least once. This choice reflects the desire to measure jurists’ appearance across the entire corpus of cases without skewing the data based on total mentions. Tracking jurist “mentions” rather than “citations” further reflects that judges do not always directly cite the jurists mentioned. For example, when citing fatwās from al-Wansharīsī’s compilation, judges sometimes quote the chain of transmission for a given rule in the legal tradition. Hence, mentions of al-Yaznāsanī (d. 1391-2), for example, are primarily from repeating al-Wansharīsī’s citation of him—a citation that the judges consciously chose to include in the rulings. Note that the analysis below does not distinguish between where the original judge versus the SCSA mentions the sources.

The 214 sources tracked in the text analysis were identified through long-term qualitative reading of the cases. It is plausible that additional jurists are cited in the SCSA corpus that have not yet been identified. Although judges mention both jurist names (e.g., Khalīl) and names of texts (e.g., Mukhtaṣar or al-Tawḍīḥ), the project counts text mentions as mentions of their author. This decision simplifies the quantitative results and reflects the importance of authorship in Islamic legal tradition. For the genre charts (below), hand-counts were performed for jurists with multiple significantly referenced texts (e.g., al-Tāwūdī and al-Wazzānī) to distinguish the intended text.

Compiling a List of Jurist Search Terms: Quantifying judges’ source mentions required compiling a list of terms by which judges referred to jurists and their texts. Creating this list through qualitative reading of the cases reflects the need to distinguish an Islamic legal tradition specifically for courts of 20th-century Morocco. The process of organizing a list of search terms for text analysis merits further elaboration:

- Common names of jurists: judges virtually never refer to jurists or their texts by their full name or title. In most cases, judges refer to jurists by their nasab or nisba. Some distinguished or distinctly named scholars are called by their given name (e.g., “Khalīl”). Rarely do judges refer to jurists by their kunya, likely due to their propensity for overlap (see “vague references” below). For book titles, jurists typically use straightforward shorthand (e.g., “al-Miʿyār” for al-Wansharīsī’s fatwā collection). The search terms do not include generic titles like “Commentary on the Mukhtaṣar” or “Nawāzil” because judges usually specify the author in such cases.

- Multiple search terms per jurist: judges could use multiple names to refer to a single jurist. For example, jurists varyingly used several names in reference to Ibn ʿĀṣim, including “Ibn ʿĀṣim,” “al-Gharanāṭī,” or “al-Mutḥaf” (literally, author of the Tuḥfa), along with multiple names for his famous text, Tuḥfat al-ḥukkām: “Tuḥfat al-ḥukkām,” “al-Tuḥfa,” or “al-ʿĀṣimiyya.” The code counts of any appearance of these terms as a mention of Ibn ʿĀṣim.

- Distinguishing common jurist names: identifying the term(s) used in reference to a jurist requires eliminating false positive results. For example, the Arabic word “mālik” could refer to Mālik b. Anas (d. 179/795, mentioned in 62 cases), or it could simply be the word “owner.” Ensuring the distinction required hand-checking every use of a search term (via word search in a text document) and marking true positives of the intended term (e.g., as Mālik1). The text was similarly manipulated to distinguish multiple jurists by the same name (for example, Shihāb al-Dīn al-Qarāfī vs. Badr al-Dīn al-Qarāfī) and similar names (e.g., Ibn Labb vs. Ibn Labāba).

- Vague and obscure references: some jurist mentions are too vague to specify the intended individual. For example, judges often cite “Abū al-Ḥasan,” a kunya carried by multiple prominent jurists on the list. There are 18 cases in which “Abū al-Ḥasan” appears without further context for identification, hence the entry “Abū al-Ḥasan – Ambiguous” on the list (not counted among the 212 sources, though they almost certainly refer to Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ṣughayyir, al-Lakhmī, or al-Tasūlī). Similarly, some names mentioned are too obscure to identify an author, especially those that are mentioned only by a single name and appear only once in the corpus (see Appendix, names highlighted in orange).

Text Preparation: The statistical programming language R was used to perform analysis on the combined texts of 777 SCSA cases. Undertaking this analysis required several preparatory steps to create a raw text corpus on which the desired analysis—tracking mentions of jurists via their search terms—could be performed. The printed SCSA records were transformed into text format using “ABBYY Fine Reader OCR” for Arabic, with 55 additional cases transcribed by hand. These case texts were combined into a single text document, where multiple hand edits were made, including:

- Correcting OCR errors: OCR leaves the possibility for flaws in rendering the correct Arabic letters, especially for those distinguished by single dots. For example, the process required checking permutations of Arabic letters ج خ and ح for each jurist or text search term, correcting “ḥalīl” to Khalīl.” Sections of cases that include jurist mentions were also hand-checked for errors, and every positive result for every term was hand-checked to prevent false positives. It is possible that false negatives remain.

- Distinguishing jurist names: as explained above, demarcating true positives for search terms in distinction from other iterations (e.g., “mālik” vs. Imām Mālik or distinguishing true positives from litigant names).

- Demarcating cases: ensuring that the Arabic text “الحكم عدد” (“Ruling Number” begins each case, as it does in the records, to distinguish each case in code as the unit of analysis.

Word Frequency Analysis with R: a series of commands in the statistical programing language R quantified mentions of the search terms per each individual case in the corpus. For details on the coding process, please see the English version of this report.

The text document was loaded into R as a character vector in UTF-8 encoding to ensure readability of Arabic text. Commands for text cleaning removed empty lines, spaces, punctuation, and diacritic marks. Since each case is demarcated with the unique phrase “Ruling Number” at its beginning, the “table()” and “grep()” functions produce an index of the cases. The text lines were then transformed into a single “string” [paste( collapse)] which is then split [strsplit()] into the cases by the phrase “Ruling Number”, each of which are then transformed into a character vector. Each of the character vectors therefore represent the text of a single case, each correlated to a number 1-777 by which terms can be tracked.

The frequency of source mentions across this corpus was calculated using the “loop” function in R based on a concatenated list of sources. The list consisted of terms associated with that source that were checked for occurrence in each character vector (i.e., the text of each case). This process produces a term frequency matrix, with the y-axis rows each representing the 777 cases and the x-axis columns each representing a source. For each jurist present in a case, the value of the given x, y becomes 1, thereby allowing for further quantification. In a similar process, the value of the x, y becomes the total number of times the jurist is mentioned in a given case.

Results and Analysis

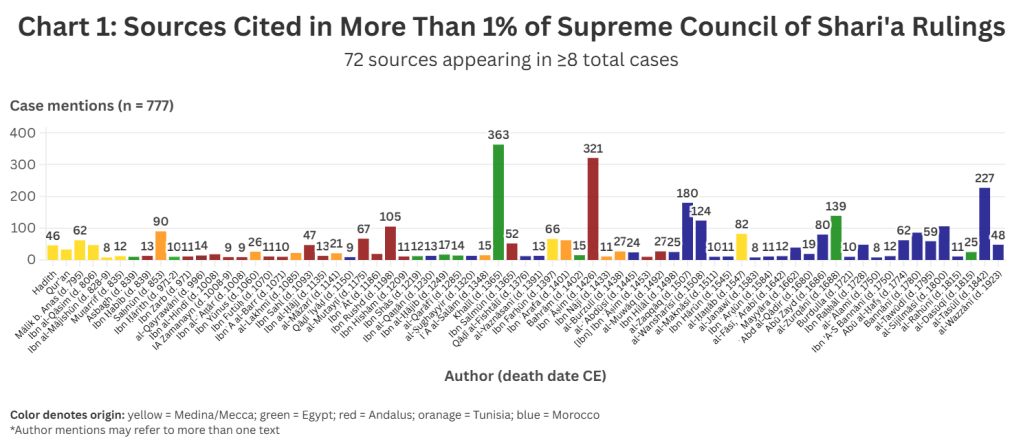

Overview: 214 individual sources (including Qur’an and hadith) were identified across 777 total cases, with 659/777 cases (84.8%) including at least one jurist mentioned. This project’s analysis focuses on the most oft-mentioned sources: those mentioned in at least 10% of cases/80 or more cases (12 sources, Chart 1) and to those mentioned in at least 1% of the cases/8 or more cases (72 sources, Chart 2). Of the 214 sources identified, 88 appear only once or twice in the entire corpus. Nevertheless, the propensity for citing seldom-cited jurists indicates the wide variety of Mālikī legal sources by which judges sought to substantiate a ruling.

Note: Charts 1-6 were made using Flourish Studio, while Charts 7-8 were made in R using the graphing tool, Plotly.

There are numerous ways by which the resulting data can be interpreted. Most importantly to “Quantifying Islamic Law” is the frequency with which the sources appear in the cases and whether any changes appear over time. Connecting jurists to their biographical data—by century, geographic origin, and genre of legal text–sheds further light on the historically expansive nature of this tradition. It remains important not to overstate conclusions from the data, which ultimately represent a limited selection of cases. Nevertheless, several important conclusions emerge that merit further discussion below.

Overall Sources

The quantitative preeminence of Khalil’s Mukhtaṣar and Ibn ʿĀṣim’s Tuḥfa confirms longstanding qualitative studies of Islamic law in Morocco. However, both texts were authored outside of Morocco (in Cairo and Granada, respectively) over 500 years before the era under study. The other most commonly mentioned jurists provide new insight into the most preeminent interlocutors of Islamic legal tradition for the judges of this data set, including:

- Bahja of al-Tasūlī (Fez, d. 1258/1842), 227 cases (29%): this 19th-century Moroccan commentary on Ibn ʿĀṣim’s 15th-century Tuḥfa is the third-most cited text overall. The text itself is clearly written and actively integrates more recent and Morocco-specific norms like Fāsī judicial practice into commentary on Ibn ʿĀṣim’s short rhyming verses. These features of the Bahja make it relevant for the contemporary Moroccan jurist and likely account for judges’ widespread reliance on it.

- Lāmiyya of al-Zaqqāq (Fez, d. 912/1507), 180 cases (23%): in Morocco, the judicial practices of Fez—the intellectual center of the region—emerged textually in three versified compilations beginning with al-Zaqqāq’s Lāmiyya. The text includes pithy verses establishing common practices that deviate from the “prevailing” (mashhūr) rule of the legal school: practices like the twelve-person testimony (lafīf), the unilateral sale of shared property (ṣafqa), and perpetual lease (zayna or jilsa). The frequency of mentioning Zaqqāq’s text, as well as authors of several commentaries, indicates the centrality of these practices to Islamic law in this context.

- Commentary on Khalīl’s Mukhtaṣar by al-Zurqānī (Cairo, d. 1099/1688), 139 cases (18%): Khalīl’s Mukhtaṣar received numerous commentaries since the 14th century, many of which received super-commentaries (including the eighth-most-mentioned jurist, al-Banānī). Many of these commentaries are mentioned throughout the cases (see Chart 3 below), and some are more renowned than others in juristic circles. However, it is clear that al-Zurqānī’s commentary was important not only for the 20th-century Moroccan judges, but as the basis for Moroccan super-commentaries on which the judges relied.

- Nawāzil of al-Wansharīsī (Fez, d. 914/1508), 114 cases (15%): al-Wansharīsī is well-known to Western scholars for his magisterial collection of Maghribi legal opinions, al-Miʿyār al-muʿrab. The expansive compilation (its print version is 12 volumes) treats the gamut of Islamic legal topics and became a quasi-encyclopedic source of precedent legal opinions in the region. While best known for its influence in juristic debates, it is clear that judges also found it worthy of mention in their rulings. Note: this does not include 10 cases mentioning his manual of documentary practice, al-Fāʾiq.

Judges relied on more recent and local interlocutors of the two most important texts, plus preeminent authors of other legal genres (e.g., judicial practiceand fatwā collections). The commentaries were not merely for understanding the texts’ language, rather they also served to update the texts with opinions and local practices that prevailed in Morocco of recent centuries. The preeminence of judicial practice and nawāzil further emphasize the integrality of such local collection texts to Islamic legal tradition of Morocco writ large. Mentions of the two core “revelation” sources of Islam—the Qur’an (33 cases, 4%) and hadith (46 cases, 6%)—occur far less frequently than the most important juristic texts.

Jurist Century and Geography

The jurists mentioned originate from the main centers of intellectual production from the Mālikī legal school: Medina, al-Andalus, Egypt, Tunis/Qayrawan, and Morocco. While total Egyptian authors are relatively few, two of them figure very prominently in the cases (Khalīl and al-Zurqānī). Andalusi authors are far more numerous, including Ibn ʿĀṣim and Ibn Rushd al-Jadd.

The chart also demonstrates the importance of Moroccan scholarship from approximately the 17th-19th centuries. This era of scholarship has received very little attention in Islamic legal studies or Islamic intellectual history writ large. However, Moroccan jurists produced prolifically during this period in a way that, as the chart shows, heavily impacted later Islamic legal tradition.

Khalīl’s Mukhtaṣar: Predominance and Perpetuation

There is no doubting that Khalīl’s 14th-century Mukhtaṣar predominated the set of 200+ sources mentioned in the cases. However, the text received numerous commentaries and super-commentaries (and even one abridgement of a super-commentary) that were critical to its perpetuation in Moroccan Islamic legal tradition. The Moroccan-authored super-commentaries produced on the Cairene jurist al-Zurqānī’s 17th-century commentary appear with relative frequency in the corpus, indicating the importance of these texts in perpetuating Khalil’s base text in 20th-century Morocco. Renowned jurist and SCSA chief judge Muḥammad al-Ḥajwī criticized the bloated commentary tradition of Khalīl’s short original text. Gannūn’s abridgement of al-Rahūnī super-commentary—a commentary on commentary on commentary—appears to bolster al-Ḥajwī’s critique.

Legal Textual Genre

Another principle finding of this study is the diversity of textual genres on which judges relied to produce their rulings. In particular, jurists who compiled precedent fatwās (nawāzil), judicial practice (ʿamal) of Fez, and manuals of documentary practice (wathāʾiq) are very well represented:

Chart 4 reaffirms that nawāzil collections were a critical feature of Mālikī law in the Maghrib. Notably, al-Wazzānī (d. 1923) is the most recent jurist cited in the entire corpus (including his other commentary works).

Chart 5 demonstrates the importance of the three versified compilations of judicial practice by al-Zaqqāq, al-Fāsī, and al-Sijilmāsī, plus their commentaries. As discussed above, these compilations were uniquely Moroccan texts that were integral to Islamic legal tradition.

Chart 6 exhibits the breadth of jurists mentioned whose texts concern documentary practice. Valid documentation was critical to the probity of legal instruments in courts of the Maghrib, including contracts, testimonies, and court rulings. In SCSA cases, judicial decisions often hinged on the probity of litigants’ documents vis-à-vis opposing evidence. As the chart shows, Andalusī jurists wrote prolifically on this matter, remaining authoritative for Moroccan judges 6-8 centuries later.

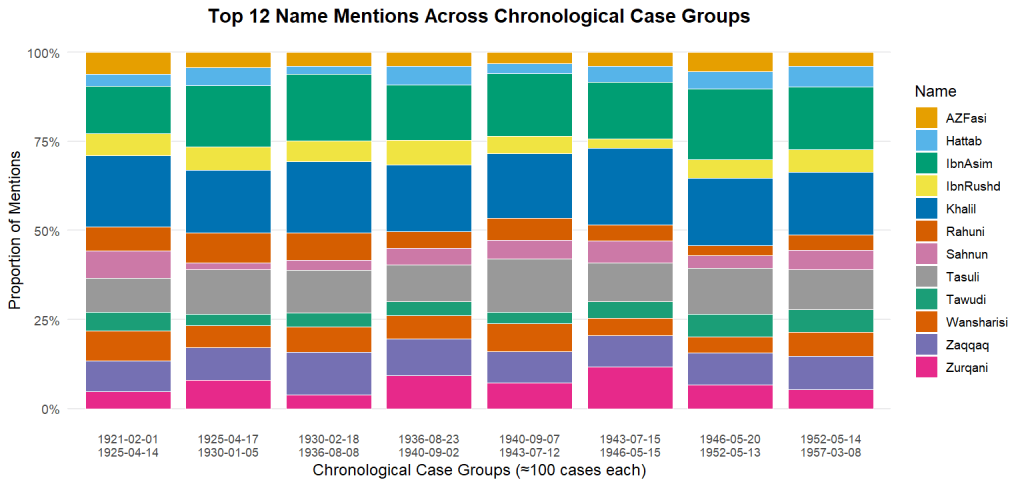

Variation Over Time

Chart 7 showing mentions of the top 12 jurists per chronological set of 100 cases over the SCSA’s existence

There is no indication that any particular source became significantly more or less prominent as a share of total mentions over time (though total sourcementions ebbed and flowed in the dataset).

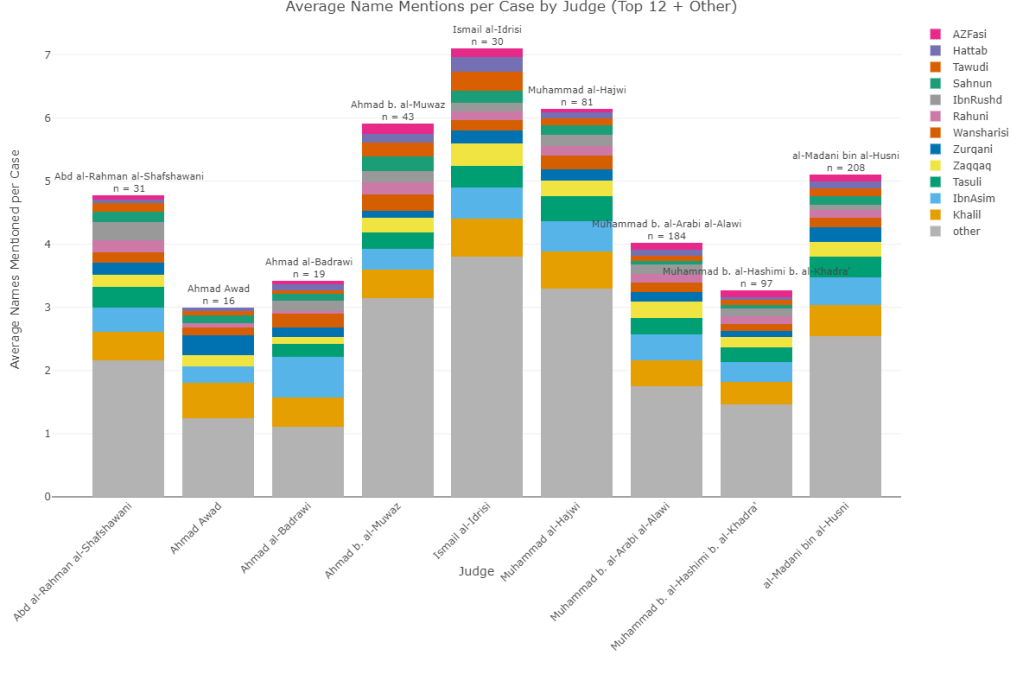

Variation by Chief Judge

Chart 8 showing average mentions of the top 12 sources per chief judges with greater than 30 cases

The dataset does not distinguish between sources mentioned by the SCSA versus the original judge, as both are included in the same case records. However, there is some indication that cases signed by certain SCSA chief judges mentioned more or fewer sources. For example, the 81 cases signed by Muḥammad al-Ḥajwī mention just over 6 sources on average; whereas the 97 cases signed by Muḥammad al-Hāshimī bin Khadrāʾ mention just over 3 sources on average. Further qualitative work would be required to determine whether individual SCSA chief judges are indeed responsible for these discrepancies.

Other Select Terminology

The project will continue to trace other terminology relevant to the study of Islamic law and court practice. Following the same methodology used to track sources mentioned, the project has performed preliminary term searches for several other important concepts in the 777 cases.

Modes of Proof and Procedure: beyond the standard testimony of two “reliable” male witnesses (‘udūl), litigants relied on a variety of other modes of establishing their claims:

- Twelve-person testimony (shahāda lafīfiyya): 429 cases = 0.55

- Oath (yamīn): 425 cases = 0.55

- Legal opinion (fatwā) presented by litigants: 261 cases = 0.34

- Royal decree (ẓahīr): 32 cases = 0.04

- Female experts (ʿārifāt) and/or midwives (qawābil): 30 cases = 0.04

- Property experts (arbāb al-baṣr): 27 cases = 0.03

Litigants: Protectorate-era legislation specified that shari’a courts were for Moroccan Muslims only, yet the records show that non-Muslims and non-Moroccans were present:

- Jewish litigants: 23 cases = 0.03

- French litigants: 16 cases = 0.02

Note: there is no dependable and efficient way to track litigant gender through term searches. One reason is simply that female litigants are extremely common.

Substantive Concepts: the presence of these terms in a case does not necessarily imply that the case focused on that issue. For example, evidence of marriage and divorce is critical to wide range of disputes concerning paternity, inheritance, and property.

- Inheritance (irātha, irth, waritha, mawrūth): 401 cases = 0.52

- Marriage (nikāḥ): 106 cases = 0.14

- Divorce by unilateral repudiation (ṭalāq), judicial divorce (taṭlīq), or repudiation for financial consideration (khulʿ): 116 cases = 0.15

- Right of first refusal/preemption (shufʿa): 100 cases = 0.13

- Accusation of encroachment (tarāmī) on property: 88 cases = 0.11

- Property pledge loan (rahn): 76 cases = 0.10

- Islamic endowments (ḥabūs): 60 cases = 0.08

- Child custody (ḥaḍāna): 44 cases = 0.06

- Enslaved mothers (mustawlida): 6 cases = 0.01

*Have you found an error in the dataset or its appendices? Would you like to see other terms run through the dataset or other types of data manipulation? Please be in touch!

Acknowledgements

“Quantifying Islamic Law” was undertaken during a two-year fellowship at Utrecht University, Netherlands funded by a Marie Sklowdowska-Curie Action. I thank Professor Christian Lange for serving as host during the project, as well as department colleagues for their feedback throughout the process. I also recognize the staff of the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies for their assistance, especially Dorieke Molenaar and Jan-Willem Bleeker.

In Morocco, I thank the staff of the Court of Cassation in Rabat and its library for providing me access to the materials used for analysis. I recognize especially Hassan Ftoukh and Khadija Ouslimane for their assistance.

I thank also Issa Nagchi, Tarik ElFalih, and Ghizlane El-Baladi for their work transcribing additional cases for the dataset, and Tarek Ghanem of Metalingual Translations who translated this project report into Arabic. I think Richard Nielsen for getting me started coding with R many years ago and the Utrecht University Center for Digital Humanities during my fellowship.

Preliminary work and design of this project were undertaken during the Arts and Sciences Fellowship at the University of Toronto (2021-2023).

Appendix: Complete List of Sources Identified in 777 SCSA Cases, 1921-1957

Note: Jurist names highlighted in orange represent the best guess of the intended jurist, absent further details from context. If you believe you know to whom the names refer, or you believe a jurist has been misidentified, please be in touch! Please refer to the subsection “Compiling a List of Jurist Search Terms” for more details.